Why Ford’s Doesn’t Produce Our American Cousin

On April 22, 1865, a group of actors prepared for an unusual performance on the Ford’s Theatre stage. Instead of performing before a full house, on this day they stood before just a few people.

This scenario may sound familiar to us during the COVID-19 pandemic. In fact, Ford’s Theatre actors took the stage this fall to film a performance of the one-act play One Destiny before an empty house.

In doing so, our actors echoed a similar performance 155 years earlier. Their predecessors, including some of the people that today’s actors portray, took the stage on April 22, 1865, performing the play Our American Cousin to an audience of Secretary of War Edwin Stanton and a host of investigators.

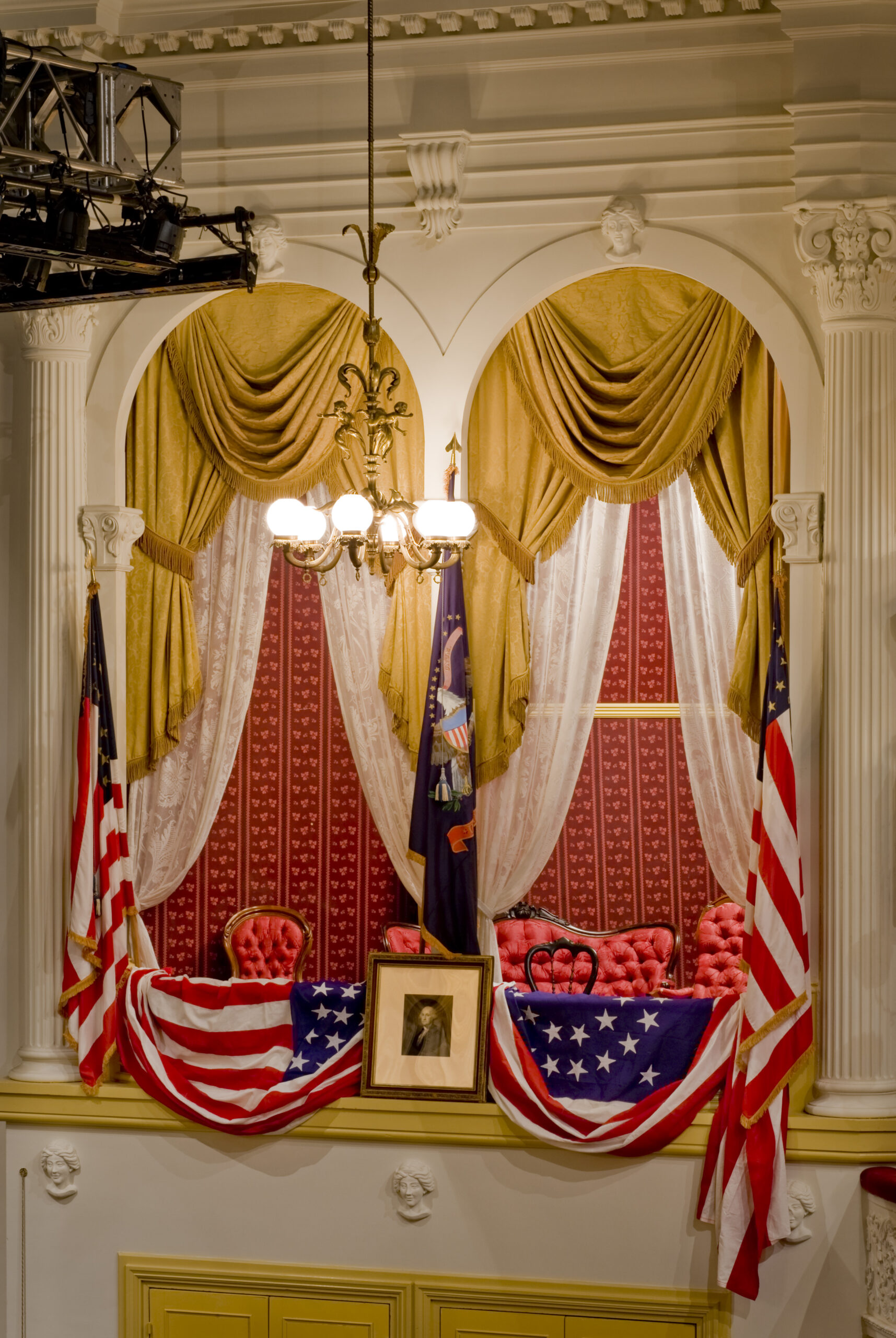

Stanton and the investigators aimed to trace what they knew of assassin John Wilkes Booth’s movements at the theatre eight days earlier—a Good Friday performance attended by President Abraham Lincoln and a packed house of nearly 2,000 people.

Through a series of twists and turns, no theatrical performance of any kind would grace the Ford’s Theatre stage again for 103 years. April 22, 1865, also became the last time that Our American Cousin was—and will ever be—performed at Ford’s Theatre.

But why don’t we perform Our American Cousin?

We at Ford’s Theatre get this question a lot. For many reasons, we do not stage reenactments of the Lincoln assassination either. Ford’s Theatre Society and the National Park Service agree that a performance of Our American Cousin in our space would also toe that line too closely.

Here are five ethical and practical reasons why not:

1. The play isn’t appropriate in the space.

When I was a child, my family and I attended a somewhat kitschy performance of Our American Cousin at Knott’s Berry Farm in California. The performance included a silhouette of Lincoln in a somewhat re-created Presidential Box.

It’s one thing to stage a performance of Our American Cousin at a theme park 2,659 miles from Ford’s Theatre, it’s another to do so in the actual space where the tragedy happened.

2. Gun violence has traumatized too many Americans.

A reason not to stage a reenactment of the assassination, much less a fully staged version of Our American Cousin, is that too many Americans have experienced gun violence. Recent studies show that historians who immerse themselves in written and oral testimonies of violence experience vicarious trauma and can suffer long-term psychological damage. What would a full-scale reenactment of a night that ended in violence do for even someone who hadn’t experienced gun violence—much less someone who had.

3. What would happen at that moment?

One of the main reasons performing Our American Cousin would come too close to reenactment is the question of what we would do at that moment in Act Three, when Booth shot Lincoln during the play’s biggest laugh line. As I recall, Knott’s Berry Farm included the sound of a gunshot at that moment, at which point the actors announced what occurred in 1865. At Ford’s Theatre, our one-act play about the people and events at the theatre that night, One Destiny, does include the sound of a gunshot as characters Harry Hawk (an actor) and theatre manager Harry Ford recount what they were doing in the moments before Lincoln was shot. Although One Destiny is staged in the space where the murder happened, the actors do not reenact Booth’s movements—he is an enigma.

On the flip side, we also must consider how it would be perceived to ignore the assassination and continue through to the true end of the play. Ignoring a violent event is just as problematic as, if not worse than, reenacting the event.

4. What would happen after that moment?

Building on that, there is also the question of what should happen after the moment when Booth shot Lincoln. Should the play go on, as it does at Knott’s Berry Farm? Should it stop, as it did in 1865 at Ford’s Theatre? Wouldn’t stopping the play defeat the purpose of putting it on in the first place? Continuing the performance would constitute disrespecting the event. Neither is a good option.

5. The humor really doesn’t land.

When Ford’s Theatre first reopened in 1968, Ford’s Theatre Society produced plays either about Lincoln’s era or plays Lincoln might have seen there. This lasted only a short time, as audiences often couldn’t connect with the plays from the Civil War era. Few plays stand the test of time.

Our American Cousin is a case in point: its class-based humor poking fun at country bumpkins and British aristocracy simply doesn’t land nor carry the attention of modern audiences. Today we produce work that draws on broad American experiences and explores aspects of Lincoln’s leadership legacy. Producing Our American Cousin not because we find it especially funny, relevant or moving but because of what happened at one performance is not in line with our mission. And that takes us back to the ethical issue.

While Ford’s interprets the moment of Lincoln’s assassination, we do not reenact it. Part of Ford’s Theatre Society founder Frankie Hewitt’s logic in restoring plays to the Ford’s stage in the 1960s was to make it once again a living, breathing theatrical space, not a time capsule of a particular moment. Staging modern plays, while acknowledging that history, is part of what makes Ford’s a living, breathing space.

Staging Our American Cousin would make Ford’s too much of a monument to what an assassin did there on the night of April 14, 1865. For all these reasons, the April 22, 1865, performance of Our American Cousin should remain the last ever at Ford’s Theatre.

David McKenzie works on exhibitions and digital history projects at Ford’s Theatre. He is also a History Ph.D. candidate at George Mason University, studying 19th-century U.S. and Latin American history and digital history. Before coming to Ford’s in 2013, he worked at the Jewish Historical Society of Greater Washington (now Capital Jewish Museum), The Design Minds, Inc. and at the Alamo. Follow him on Twitter @DPMcKenzie.