Following a Historical Figure, Again: Prototyping Sprint 3

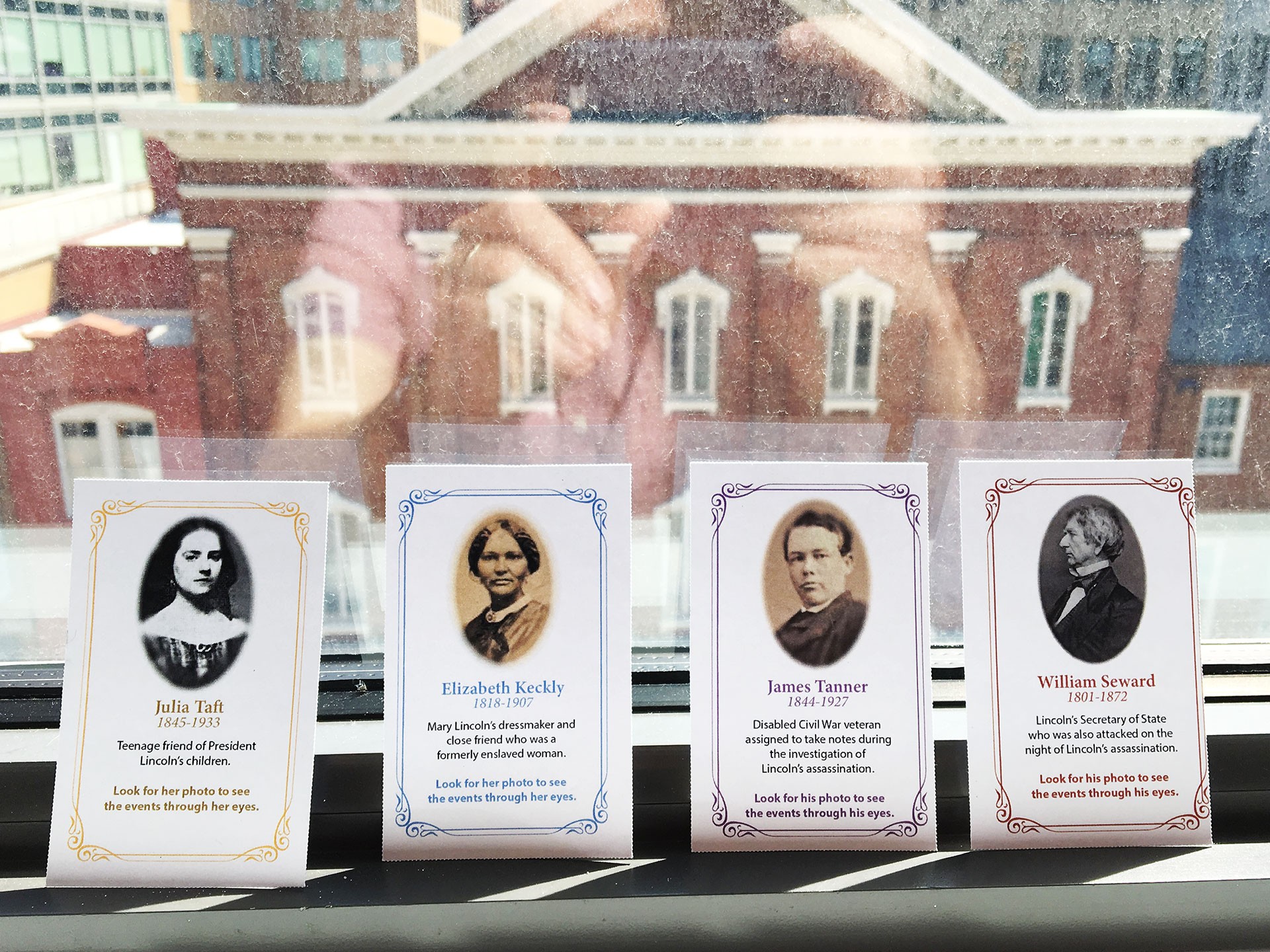

Student groups visiting Ford’s Theatre on the mornings of Thursday, May 17, and Thursday, May 24, 2018, got something that visitors normally don’t receive: Character cards, in the style of trading cards, with pictures of historical figures. Students then entered the Museum to find flip doors that shared stories about each person.

This was the third and final sprint of our prototyping project, Design Research at Ford’s Theatre (D.R.A.F.T.). Our team comprised several Ford’s staff members and Kate Haley Goldman, facilitator and evaluator.

- Introduction to the prototyping process

- Sprint 1, Round 1

- Sprint 1, Round 2

- Sprint 2, Round 1 (part 1) (part 2)

- Sprint 2, Round 2

Iterating on an Old Idea

For the last Sprint rounds, the team decided to pursue one of our prior ideas, with the goal of readying a concept for high-fidelity testing. We kept to low-cost concepts we could implement in the short-term. We began with the character cards, the concept where we’d seen the most student engagement.

We’d already tried the character cards once, and we were keen to iterate on that idea. See our previous blog post for more information on our first design of the cards. When we came back together, we looked at the previous concept and came up with changes for the next round of testing. Read on to see what we changed in each round, and what we learned.

Sprint 3: Round 1

What We Changed

- Because visitor services staff and NPS Rangers found cards left throughout the theatre in the previous round, we added a spot for students to return the cards for recycling. We repurposed a donation box in a stairwell landing.

- Students reported desiring more stops per character and were often confused by inconsistencies in the number of stops—some had three, while others had four. Associate Director of Visitor Operations Allison Alonzy’s suggestion, we tried having five characters with five stops each. Based on feedback from the previous round—that students needed a sense of completion—we added an indicator of what stop number each flip door was: “Stop 1 of 5.”

- We added Tad Lincoln as a fifth figure. Students reported an interest in learning more about his story.

- On a regular day, rather than having someone stationed to talk with group leaders, we would need to rely on our box office staff to distribute the cards when they distribute tickets. So, we tested that.

- After debating whether to go with a digital option, we kept the physical flipping of doors but made them more hefty this time—using foam board. This more closely simulated how they might be built in the future.

What We Learned

- Students indeed recycled the cards in the donation box.

- After recycling the cards, the students did leave with a feeling of, “That’s it?” The group discussed how to make a “payoff” at the end, to offer a sense of completion and accomplishment.

- Five stops with five historical figures seemed the right number. Having the stop numbers out front seemed to give students more of a sense of completion—but the stop numbers were not prominent enough in a dark museum space.

- Engagement in this round seemed strong, as it had in the previous sprint. Again, though, we noticed variation based on the priming that a tour guide gave. Also, some groups print their tickets at home, so we still needed a staff member in the lobby to hand out cards and explain them.

- One unresolved question that came up was whether this activity increased or decreased engagement with other exhibition content. So, rather than each flip door hinting at the storyline of the next flip door, we decided to try putting a hint about the location in the museum to find the next flip door.

- The stories overall seemed to resonate with students. But that didn’t mean we had the right mix of figures—particularly, not enough young people.

- Initially we tried to keep text minimal—no more than 50 words per flip door. Interestingly, and against what is often exhibition writing best practice, students reported wanting to learn more about the person on their card. So, we discussed options such as adding online content or audio, but knew that we couldn’t do so in the next round due to a short timeframe and lack of equipment.

- This activity seemed to engage students in the museum space, but we still found that the question of relevance remained open.

Perhaps most importantly, we learned that this experiment was worth iterating. Initially we had planned to re-test the ballot idea from the previous sprint. Instead, we chose to repeat this experiment, with some more changes based on what we learned.

Sprint 3, Round 2

What we changed

- We added to the cards’ instructions to be slightly clearer about what the students were supposed to do in the museum.

- We added an onboarding poster as they descended into the Museum to address the varied group experience with tour guides or teachers. Some groups had a briefing prior to entering the Museum, where they had a chance to look at their card and hear what the activity involved. Other groups had a card handed to them at the last minute when they were entering the Museum. The poster was designed for these groups, so they would have a prompt to start searching for their character.

- We chose consistently younger historical characters by adding Fanny Seward and Anna Surratt. The narratives for both of these individuals are strong, compelling stories and tied directly to the assassination.

- We placed the fourth stops all together near the stairs to the theatre, to signal that the fourth stop is the moment just prior to the assassination. The fifth stop for each was elsewhere, primarily in the area where the assassination aftermath content was located.

-

In response to student and tour guide feedback in the prior round, we developed a “payoff” for the completion of the activity– students could use their card to vote. There were two voting options, and we tested each on different groups. Some students voted on whether they liked the activity, the others on whether they understood what it felt like to be that character.

What We Learned

- Engagement varied with the level of introduction the groups received. Nonetheless, students were actively seeking out the stories and at times went on to follow more than one story.

- The onboarding elements seemed to help students know what to do. Those students who did not participate still had a clear sense of what the activity was. Some adult visitors were confused by the signage. Most adults not with a school group did not engage in the activity.

- Five characters with five stops each is the maximum amount of content we can add to the existing Museum without overcrowding the Museum.

- Having younger characters and more female characters supported student engagement. Students were intrigued by Anna Surratt’s relationship with the conspirators, and advised us to keep her as a character.

- The card recycle box still needs fine-tuning. The boxes themselves should not be recycle bins (which we used for the experiment), as students did not focus on the “voting” portion of the activity unless prompted, instead simply dropping their card in the most convenient bin.

- Voting itself was a trigger word for tour leaders and teachers, who expressed some alarm the students would be asked to vote. This alarm was dispelled once we explained the concept, but in the future we should perhaps not phrase the reflection moment as a vote.

- While voting did seem to be a completion to the activity, the team felt the payoff was not sufficient.

- Placement of fourth and fifth stops was confusing to visitors, and our central concept of having them focused on the assassination content as they move into the Theatre was not clear to students.

Next Steps

- The character cards are clearly working. We will move forward with developing five or more cards, with the understanding that only five will be used in the Museum at any one time. The team could cycle through individuals to be used.

- The team is interested in perhaps changing the terminology, as “character” sounds fictional. Persona is one possibility, as the students were familiar with that term.

- The box office can continue to distribute the cards to tour leaders as they check in. It’s helpful to have staff or rangers brief the group but not required.

- The “payoff,” whether voting by another name or some other form of payoff such as a selfie station with the character, needs to be revised. The placement of this “payoff” also needs to be revised.

- The positioning of the fourth and fifth stops of each character needs to be revised. While it was useful to have a stop with each character represented, the overall flow—having to go backward in the Museum from steps four to five—was flawed.

- Extended content in the form of a button to push at a stop in the Museum with more information on each character, or further information online, would be useful. Some students looked up Fanny Seward’s diary online, suggesting they may make use of online content. Since some teachers asked for historical figure cards, the team was also interested in posting the character cards online in the future.

This round of testing concluded our prototyping in sprint format. Look for our upcoming blog post on how conducting Sprints impacted Ford’s Theatre and our perception of prototyping.

David McKenzie is Associate Director for Interpretive Resources at Ford’s Theatre. He also is currently a History Ph.D. candidate at George Mason University, studying 19th-century U.S. and Latin American history, as well as digital history. Before coming to Ford’s in 2013, he worked at the Jewish Historical Society of Greater Washington, The Design Minds, Inc. and at the Alamo. Chat with him on Twitter @dpmckenzie.

Kate Haley Goldman is an Evaluator and Strategist, currently working with Ford’s Theatre Society, Lower East Side Tenement Museum, AAAS, and others. She works on projects with difficult cultural history, citizen science, digital storytelling, data-based decision-making, institutional capacity building, and long-term visitor outcomes. Chat with her on Twitter @KateHG4.