Finding Black Witnesses to the Lincoln Assassination

Joe Simms was stunned by what he saw. Like most nights, he was working as a stagehand at Ford’s Theatre. That night’s play—Our American Cousin—was coming along fairly routinely. As someone working in live theatre, Simms knew to expect the unexpected; but he didn’t anticipate what he saw near the end of the third act.

“Nearly at the end of the third act I heard the report of a pistol, and immediately I looked across. I knew it was something strange for anything like that to occur in front of the stage among the people. I looked and saw a man jump down from the private box on the stage with a knife in his hand about a foot long. As he rose after the leap he turned his back on the private box and said something like ‘revenge for the South’ and made his escape across the stage and out at the back door.”

Joe Simms

Around the same time, Mary Anderson was standing at her front door, looking into Baptist Alley behind Ford’s Theatre. Suddenly, she saw a man run out of the theatre’s back door.

“I was looking through the open door & noticing the people moving about behind the scenes from time to time, when all of a sudden I saw [John Wilkes] Booth burst into the passage as if coming from the stage, & rush to the back door like lightning. He had his right arm up above his head and held something in his hand that glittered in the gaslight. His other arm seemed to be held out back of him. He had no hat on. As he came out of the door to his horse, I saw him strike at somebody & then leap on his horse & gallop down the alley. I thought the horse had run away with him. There was immediately a great excitement and people ran out into the alley.”

Mary Anderson

Anderson and Simms were among the small number of Black employees of Ford’s Theatre in 1865. The theatre reflected the city’s racial hierarchy—one that activists were working to change—and perhaps also reflected theatre owner John T. Ford’s Confederate leanings. Black employees at Ford’s Theatre worked in lower-level positions—as cleaners like Anderson, stagehands like Simms, and those who worked in the fly gallery above the stage, raising and lowering scenery like John Miles.

Like other employees and audience members of Ford’s Theatre, they witnessed an extraordinary event when John Wilkes Booth shot President Abraham Lincoln on April 14, 1865.

Over the next days and weeks, Anderson and Simms talked with investigators. Typically, investigators took depositions from people they interviewed. Other times investigators received letters from people with tips.

In addition to Anderson, Miles and Simms, many Black Washingtonians shared publicly what they saw. Robert Nelson found the knife that Lewis Powell used to stab Secretary of State William Seward. Sisters Nancy and Ann Brown suspected that their pro-Confederate neighbors, Mary Cook and James Owner, were at least guilty of treason, if not involved in the Lincoln assassination plot, for celebrating Lincoln’s death and closing the blinds when a mysterious man arrived at their house.

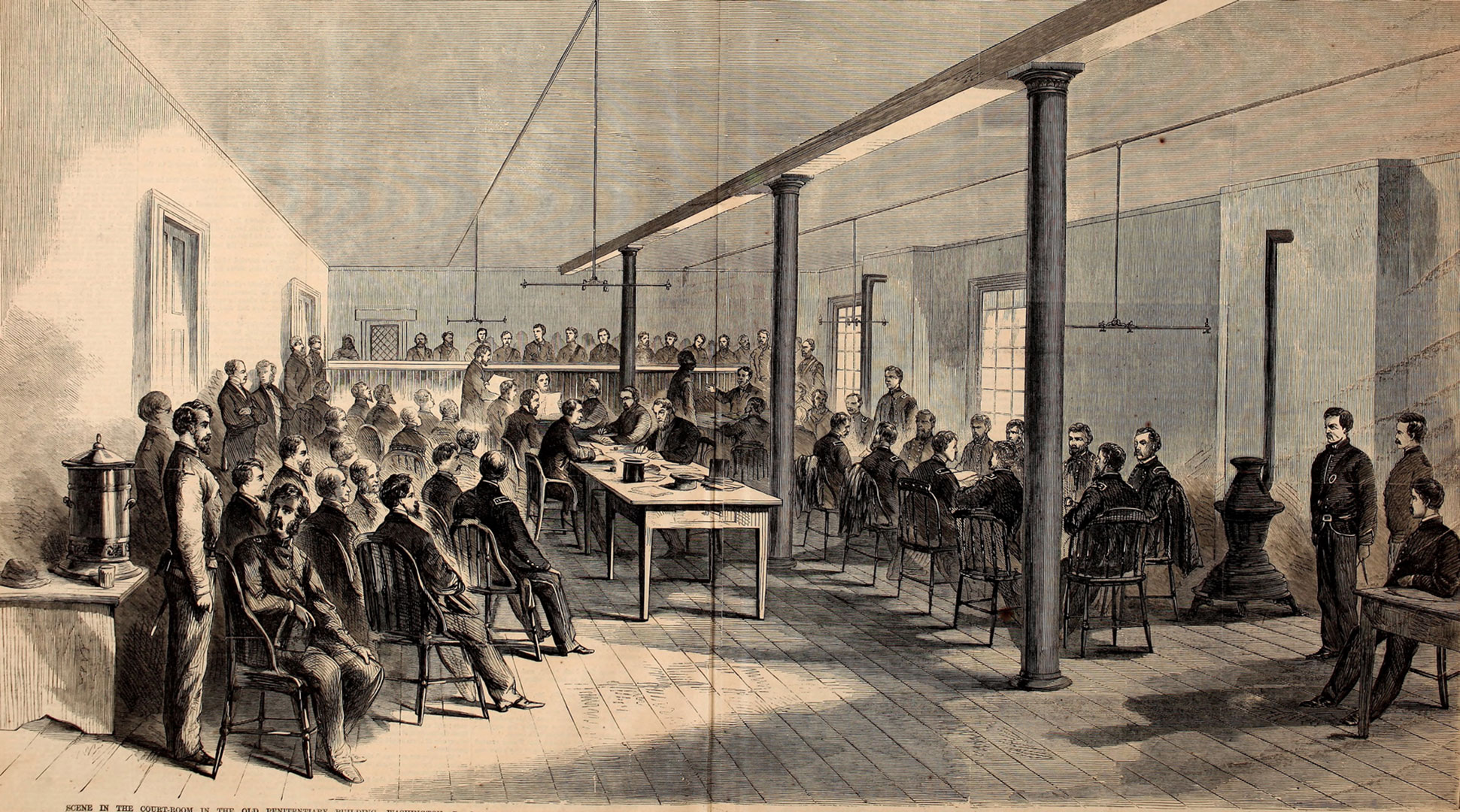

Eight conspirators went before a military tribunal in May and June 1865. As with most trials, reporters quickly took notes on, and in some cases transcribed, witness testimonies. The Lincoln assassination trial was one of the first times that Black Americans were allowed to testify against white Americans in open court. Witnesses included several people whom Dr. Samuel Mudd had formerly enslaved.

Racism in Archival Records

How do we know the stories of Anderson, Simms, Miles, Nelson and the Brown sisters? And how do we know their racial backgrounds?

Quite often, the stories of Black Americans from this time period—especially in their own voices—are not easy to find directly, much less comprehensively. As historian Kidada E. Williams notes in character spotlights for the Seizing Freedom podcast:

“With the exception of a few lengthy autobiographies, the stories we have about African Americans from these eras are most often snippets from newspaper articles, or letters without context, or testimonials given in court, or interviews conducted and ‘translated’ by government agents.”

Kidada E. Williams

Even when Black people wrote in their own voices, many mainstream archives did not collect and keep those records. Archivist Ashley Stevens, creator of the “Archives Are Not Neutral” campaign, the Alabama Department of Archives and History (in its Statement of Recommitment in June 2020) and many others have discussed how archives frequently chose to prioritize the collection of documents, stories and artifacts of wealthy, well-connected white people.

Investigators and reporters who transcribed the assassination’s military tribunal testimonies indicated when a witness was not white, usually with a parenthetical saying “(colored)” by the person’s name. Unsurprisingly, the same was not done for white people—implying whiteness was the default assumption, whereas Black people needed to be identified as such.

Due to a racist practice in creating the historical record of the Lincoln assassination, Black voices are now relatively easy to identify.

Identifying a Problem

Since launching a new website design in late 2016, Ford’s Theatre Society has built an online exhibit on the Lincoln assassination emphasizing first-person accounts of the event. Several interns and I scoured the historical record, thinking about what stories we wanted to tell and what primary sources would help tell that story.

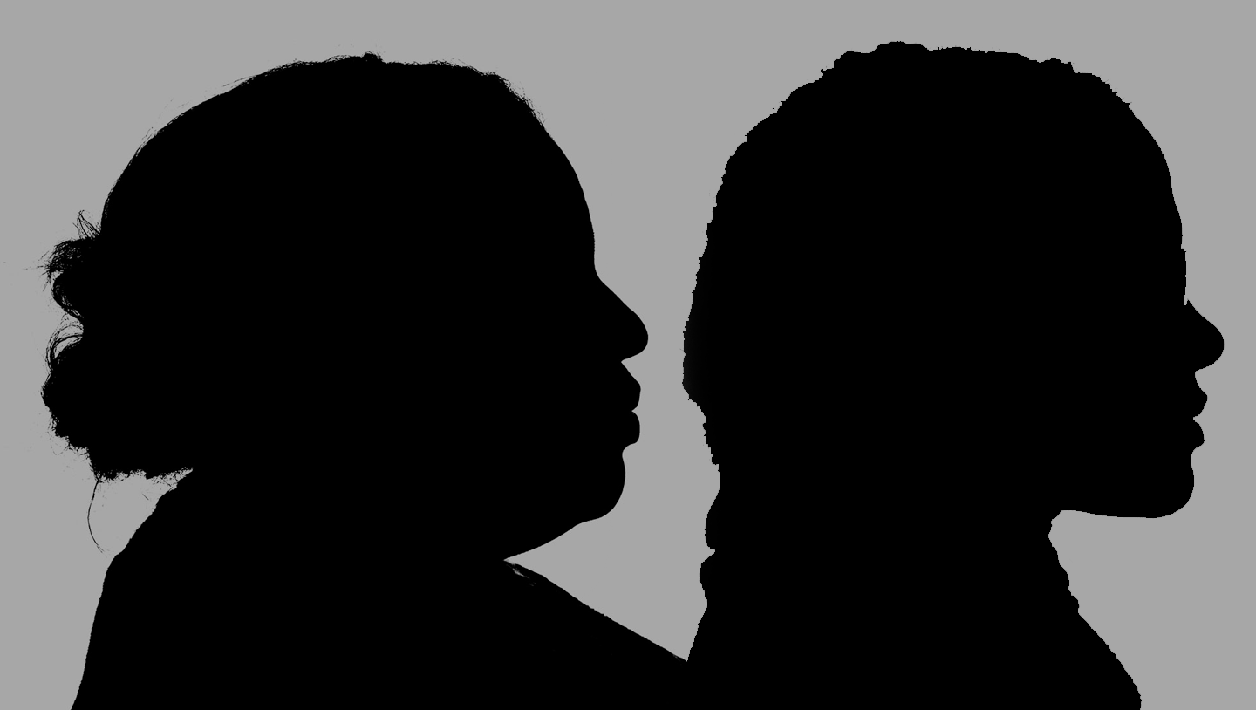

As we built out the website, we made the mistake of using a “generic” but white-presenting silhouette to represent people whose images we did not have. This was something that other staff members, advisors and Ford’s Associate Artists rightfully pointed out. Gary Erskine, our ever-creative design director, suggested we create silhouettes similar to those that our colleagues at Mount Vernon use to represent people for whom they don’t have pictures. Staff members at Ford’s, particularly Black staff members, offered their likenesses as silhouette models.

History interns Dakota Harrington and Amber Darby tracked down enough demographic information (gender, age and race) about those people in the historical record that we could create relevant silhouettes.

This exercise also gave us a chance to audit whose voices our online exhibit represented. The results did not represent the diversity of people living in Washington in 1865 nor those who shared their experiences about the Lincoln assassination. The city’s already-sizable Black population (the vast majority free, even before the Civil War) grew in the 1860s as people emancipated themselves from slavery and as Black men joined the U.S. Army in droves.

Thus, we made an intentional choice to better represent the people of 1860s Washington.

Adding Black Stories

As we combed through the historical record of the Lincoln assassination, we specifically looked for stories shared by people labeled as “colored.” Many of these records are digitized with keyword searchability. In doing, we have made use of the racism present in the historical record to facilitate our telling of more diverse stories.

We encourage you to check out the Lincoln’s Assassination section of our website to learn about some of the Black Americans, like the Brown sisters, Miles, Simms and Henry Woodland, who intersected with the Lincoln assassination story. If you want to know more, check out the digitized primary sources (detailed below). Just remember what Williams said about sources like these—they don’t tell the complete story of a person’s life and are filtered through white transcribers. Nonetheless, they do provide us with glimpses.

David McKenzie works on exhibitions and digital history projects at Ford’s Theatre. He is also a History Ph.D. candidate at George Mason University, studying 19th-century U.S. and Latin American history and digital history. Before coming to Ford’s in 2013, he worked at the Jewish Historical Society of Greater Washington (now Capital Jewish Museum), The Design Minds, Inc. and at the Alamo. Follow him on Twitter @DPMcKenzie.

Thanks to Lauren Beyea, Kristin Fox, Sarah Jencks, Liza Lorenz and Erika Scott for their thoughts on this post.

For Further Reading

Reporter Ben Perley Poore’s transcript of the Lincoln assassination trial—considered the most reliable—is available and searchable on Internet Archive. This work is possible thanks to the Allen County Public Library (Indiana), which holds and makes available the Lincoln Financial Foundation Collection. You can read and search volume one and volume two.

Additionally, historians William C. Edwards and Ed Steers transcribed the depositions and letters accumulated during the investigation—held in the U.S. National Archives—and made them available in book format. The National Archives contracted with Fold3—now part of the conglomerate Ancestry.com—to digitize the microfilm of these records, which are now searchable as well.