Adapting School Programs to serve English Language Learners

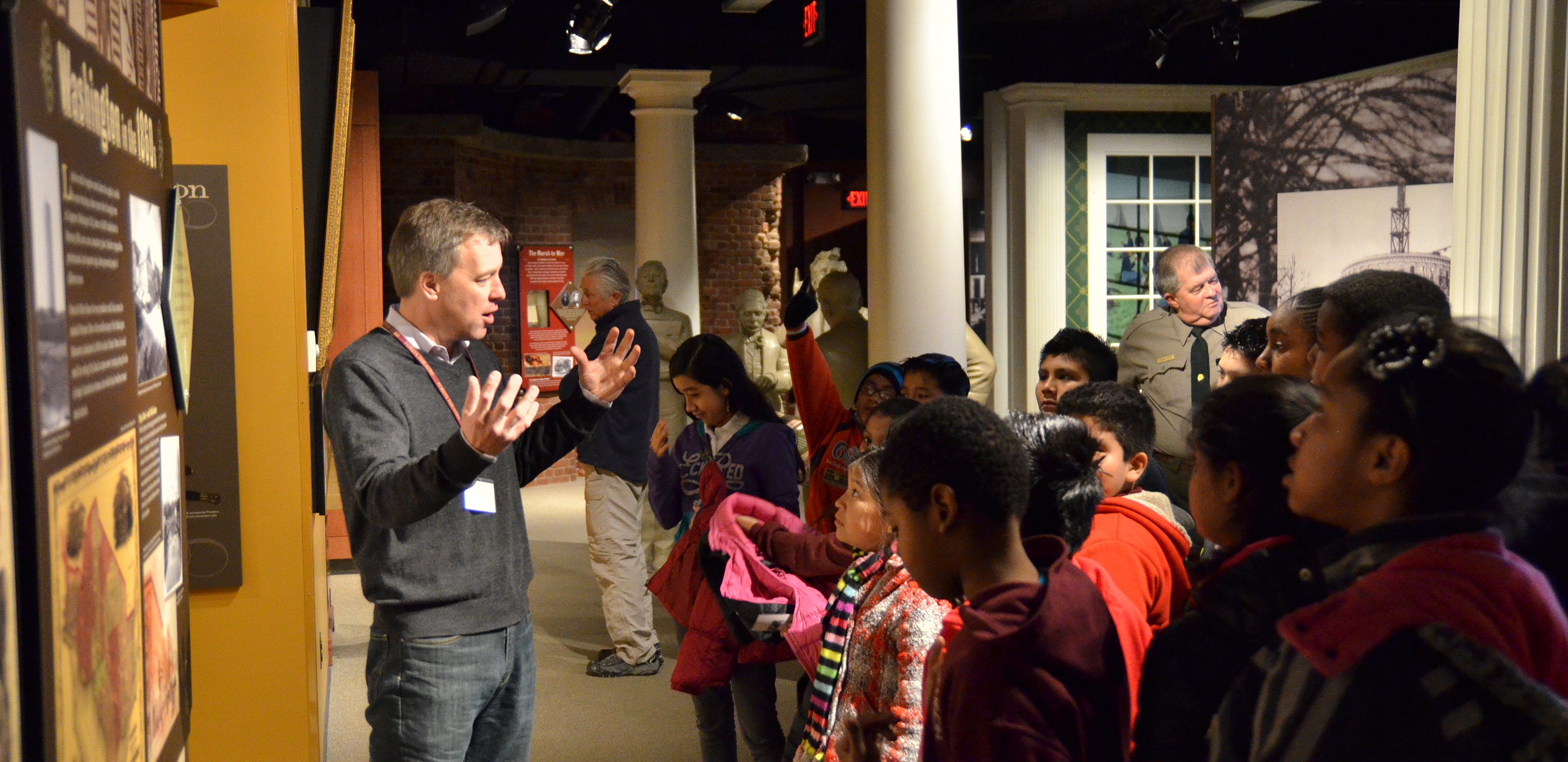

We all have wish lists for how we’d like to transform our institutions. For me, making Abraham Lincoln’s legacy more accessible to English-language learners (ELLs) is a priority. I want all of our students to understand President Lincoln’s words and messages. I believe that language should not be a barrier to experiencing the power of Lincoln’s words. Rather, it can be the gateway.

Step One: Reflecting on Our Programs

Our education programs serve students from a variety of countries. According to the American Community Survey, one in five U.S. residents speaks a language other than English in the home. In my almost 10 years at Ford’s, I’ve interacted with ELL students in local public charter schools as well as students in D.C. Public Schools, Prince George’s County Public Schools, Montgomery County Public Schools, D.C. Public Schools, Alexandria City Schools, Arlington County Public Schools and Fairfax County Public Schools.

Twenty-one percent of the student population in DC Public and Public Charter schools combined are ELLs, and nearly 30 percent of the student population in Alexandria City Schools are ELLs. In DCPS alone, there are 147 different home languages represented in its ELL population. With that many ELLs already visiting Ford’s, my goal has become finding ways to ensure that ELL students have a worthwhile experience both when they visit and when they work with our teaching artists in their classrooms.

Step Two: Forming Vital Partnerships

On her MuseumTwo blog, Nina Simon, Executive Director of the Santa Cruz Museum of Art and History, frequently discusses a common mistake made when reforming an institution. She writes that management too often decides what changes should be made before asking the targeted community what changes they need. To be successful in adapting our programs to serve ELLs, I knew I needed to ask ELL teachers what they wanted and needed to make their students feel included.

The Lincoln Oratory Festival is a small enough program that we can try out adaptations and learn from the experience before applying methods to our programs at large. Participating classrooms in this D.C.-area program receive five visits from a Ford’s Theatre Teaching Artist, who helps the class learn and perform one of Lincoln’s speeches on our stage. To consider adaptations to this for ELLs, I met with Katherine Felter, a former teacher of ELLs. Currently she serves in the role of Global Studies Coordinator at MacFarland Middle School, supporting teachers and students to develop their global competencies. I wanted to discuss how Ford’s could best serve her students in our Lincoln Oratory Festival.

I went into this meeting convinced that Ford’s would help Ms. Felter’s students build vocabulary and strengthen their English fluency, and that these were the outcomes that would be most important to her. While fluency and vocabulary acquisition were important outcomes to Ms. Felter, they weren’t the primary outcomes she was hoping our program would offer her students. “Oh, don’t worry about vocabulary. That’s my job,” she said.

Instead, Ms. Felter’s recommendations were to help her ELL students understand the context of the Civil War and Lincoln’s leadership. If they could begin to understand the concepts behind the words, their experience in the program would be a success.

With these goals in mind, I spoke with our teaching artist, and we came up with a plan to better emphasize our program’s historical context.

Step Three: Create Materials Specifically Designed for ELLs

It will take time to translate our education materials into multiple languages, but we have begun Spanish translations of our most essential oratory print resources and will address other translations as needed. However, creating translations is only one part of our intentional approach.

We were encouraged by Ms. Felter to include visuals with the speeches we teach to enhance student understanding. Visuals help ELLs associate a concept with a word easily and quickly. These students do understand complex concepts but may not yet have the English language fluency to communicate their understanding.

So, by using an image of the Gettysburg battlefield when teaching Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, we can ask, “What do you see?” and students can identify things they know and build vocabulary for things they do not. Through this approach, ELLs begin to make the connections with the Civil War, the Gettysburg Address and the themes of the speech, without having to struggle with unfamiliar vocabulary.

Our program also uses tableau vivant as a way for students to demonstrate their understanding of a speech. In tableau, a group of students create a “living picture” with their bodies to communicate an idea. We discussed this with Ms. Felter, and she confirmed that it’s great for students to “show what they know.” Like photographs or paintings, creating a tableau enables ELLs to demonstrate more easily what they want to communicate, since they don’t have a lot of words in English to do so. Students can use gesture and posture, create shapes with their bodies or use levels (low, middle, high) to communicate their understandings. This is a helpful starting point for discussion.

Step Four: Changing the Picture of Success

We know that students who see themselves in the content retain what they’ve learned long-term. To that end, we and our teaching artists encourage ELLs to say words or phrases from Lincoln’s speeches in their home language as part of their Festival speech performance. This gives students another opportunity to confidently speak Lincoln’s words aloud and reaffirms for listeners how the ideas contained within Lincoln’s speeches are meaningful and resonate with people across borders.

A student speaking “Of the people, by the people and for the people” from The Gettysburg Address in her home language of Spanish or Vietnamese is, we now feel, the true expression of those words.

Assessment

As we take these initial steps to adapt programs to better serve ELLs, we know it is crucial to evaluate the process. During the school year we will continuously check in with Ms. Felter and her students and will have them complete a post-program survey, offered in English and in Spanish, to measure how closely we achieve student learning outcomes. With their feedback we can continue to adapt to what best serves our ELL students’ needs.

If we take the time to be intentional and to really listen to ELL students we serve, we’ll be able to help them use Lincoln’s words to become confident speakers of a second language and engaged participants of the country he once called an “inestimable jewel.”

We realize that this effort will be ongoing and ever evolving. I’m sure we will learn a lot about what works and what can be improved to better serve an important part of the student population. I’m excited that we have an opportunity to reach many more students and to make our programs more inclusive and accessible. These small, intentional changes have the potential to be transformational!

Cynthia Gertsen is Associate Director for Arts Education. She presented about this topic at the 2018 American Association for State and Local History (AASLH) conference in September.